With unsafe abortions contributing to 18% of maternal deaths, Malawi finds itself facing a dilemma in achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of reducing maternal mortality to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030. Brian Ligomeka writes.

Sitting on the veranda of her house in Bangwe Township, located in the southern Malawian city of Blantyre, 56-year-old Manesi Kamolo sheds tears as she recounts in an interview how her 17-year-old daughter died.

According to Kamolo, her daughter became pregnant after being raped while returning from school. “My daughter revealed to me that she was pregnant as a result of the rape,” she explains. “The discovery of the pregnancy haunted her. She told me she never wanted to keep the pregnancy as she wanted to continue with her education.”

Kamolo adds, “One Wednesday night, I heard her groaning in her room. Upon checking on her, I found her bleeding. I thought it was a miscarriage. It was at the hospital, after a medical examination, when I learned that my daughter had attempted to induce an abortion using some objects.”

According to Kamolo, her daughter died while health workers were providing post-abortion treatment. She wonders why the government outlaws the provision of safe abortion services to rape victims like her late daughter, only offering post-abortion treatment when the consequences of an unsafe abortion are already being suffered.

Kamolo’s daughter is not the only girl to die due to pregnancy-related causes in Malawi. The Ministry of Health reports that out of every 100,000 live births, 349 women and girls die due to pregnancy-related causes. Unsafe abortions account for 18% of these maternal deaths.

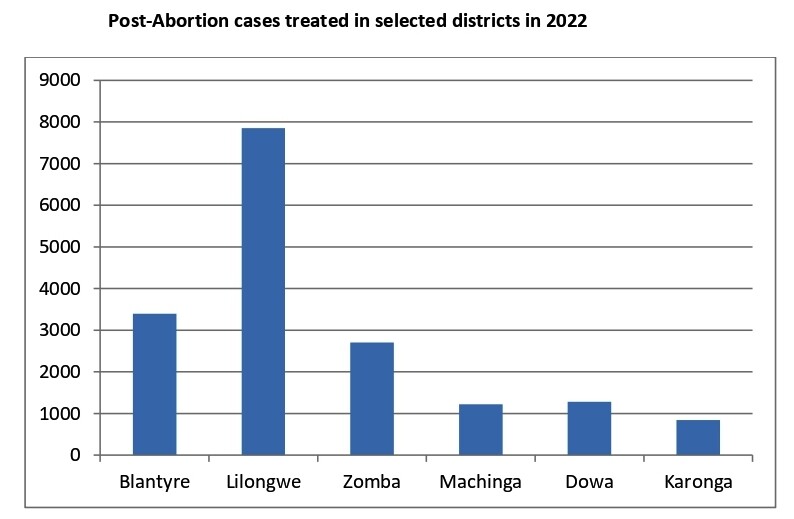

Magnitude-wise, data compiled by Ipas Malawi reveals that in 2022 alone, 3,395 women and girls induced unsafe abortions and sought treatment at post-abortion clinics in district health facilities. The increase in the number of those seeking post-abortion treatment is not unique to Blantyre. While health facilities in Blantyre provided post-abortion care to 665 women in 2020, the number rose to 1,144 in 2021 and further to 3,395 in 2022.

A similar trend is observed in Lilongwe, which recorded 1,098 cases in 2020, 4,711 cases in 2021, and 7,851 cases in 2022. The trend is also present in rural districts such as Rumphi, which recorded 327 post-abortion cases in 2020, 448 cases in 2021, and 569 cases in 2022.

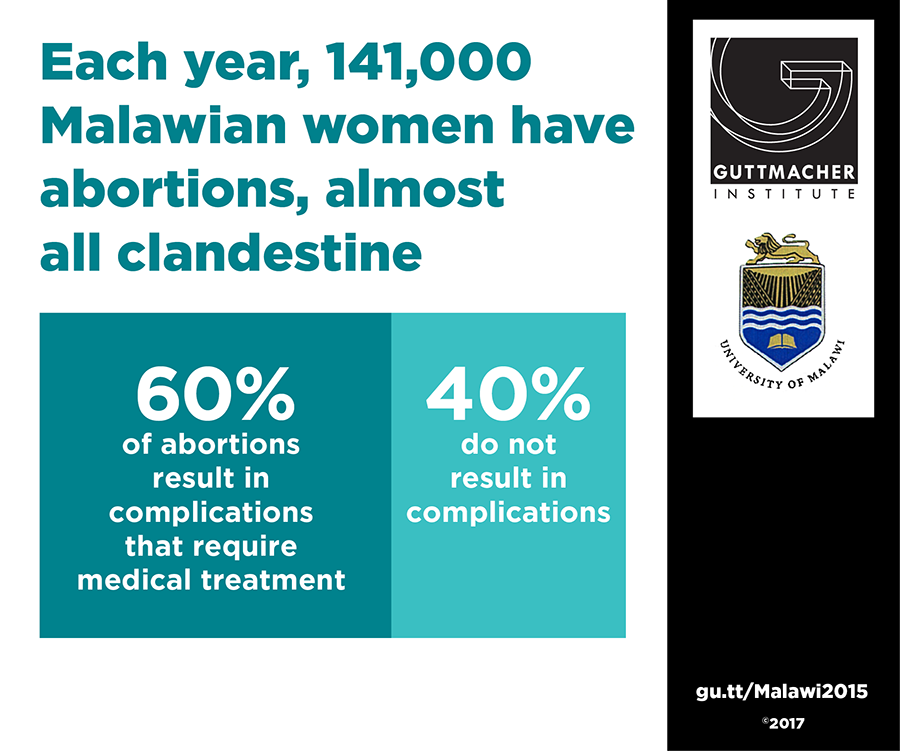

At the national level, research conducted by the Guttmacher Institute and Malawi’s College of Medicine revealed that in 2015 alone, over 141,000 women and girls induced abortions in Malawi.

Reproductive health and rights activists attribute the increase in unsafe abortions to restrictive laws. Emma Kaliya, Chairperson of the Coalition for the Prevention of Unsafe Abortion (COPUA), states that the criminalization of abortion in nearly all circumstances forces women and girls to seek desperate and unsafe methods to terminate pregnancies.

Kaliya says, “Most of the time, when women decide to terminate unplanned pregnancies, restrictive laws fail to stop them.”

The need for abortion law reform is justified in the Report of the Law Commission on the Review of Unsafe Abortion, which states: “For a long time, the Government has bemoaned the high prevalence of maternal mortality in Malawi and has identified unsafe abortion as one of the major contributing factors to this problem… In this regard, some commentators have faulted the restrictive law on abortion and the criminal sanctions that follow as contributing factors to the problem of unsafe abortion in Malawi, apparently because women, for fear of the law, resort to clandestine and unsafe means to terminate unwanted pregnancies. Such commentators, including the Ministry of Health, called for a review of the law on termination of pregnancy.”

Realizing the magnitude of unsafe abortions, Malawi drafted the Terminations of Pregnancy (T.O.P) Bill as an effective response to maternal deaths caused by backstreet abortions. However, despite initial support from state actors such as the Ministry of Health and the Malawi Law Commission, the government has grown hesitant due to opposition from religious leaders.

The painful reality of the problem remains evident in hospitals. While the government procrastinates in enacting the bill, gynecological wards are filled with women and girls suffering complications from backstreet abortions. The increasing statistics of mortality and morbidity resulting from unsafe abortions contradict the government’s declaration in the National Post Abortion Care Strategy that “no woman should suffer or die from complications of abortion in Malawi.” Merely offering post-abortion care to women injured during backstreet abortions is an inadequate piecemeal solution to prevent maternal deaths.

The draft abortion bill, if enacted, would allow women and girls access to safe abortions to prevent harm to their physical and mental health, as well as in cases of severe fetal malformation, rape, incest, and defilement. However, the bill currently gathers dust at the Ministry of Health offices.

When asked about the prospects of the T.O.P Bill, Kaliya observes, “In Malawi, all laws related to women’s empowerment face stiff resistance and sometimes take years to be enacted. Patriarchal forces disguised as culture, morality, and even religion oppose gender equality and equity reforms.”

Citing examples of the Gender Equality Act, the Marriage, Divorce and Family Relations Act, and the Prevention of Domestic Violence Act, which faced significant resistance from patriarchal individuals in Malawi, Kaliya remains optimistic. She says, “Just as determination enabled us to push for the enactment of several gender equality laws, we will fight hard to ensure that the T.O.P Bill is enacted. It may not be today or tomorrow, but one day it will be enacted,” says Kaliya, a long-time gender activist.

For Kamolo, the sooner the abortion law is liberalized, the better, so that women do not end up in graves like her daughter. While Malawi has made progress in reducing maternal mortality by addressing certain causes such as severe bleeding, infections, eclampsia, and obstructed labor, the issue of unsafe abortions remains unaddressed. Without tackling unsafe abortions through law reform, Malawi’s aspiration to reduce maternal deaths to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals, will remain a distant dream.

Brian Ligomeka leads the Centre for Solutions Journalism, a human rights media organization based in Malawi.