Amnesty International announced today that it has withdrawn its highest honour, the Ambassador of Conscience Award, from Aung San Suu Kyi, in light of the Myanmar leader’s shameful betrayal of the values she once stood for.

On 11 November, Amnesty International’s Secretary General Kumi Naidoo wrote to Aung San Suu Kyi to inform her the organization is revoking the 2009 award.

Half way through her term in office, and eight years after her release from house arrest, Naidoo expressed the organization’s disappointment that she had not used her political and moral authority to safeguard human rights, justice or equality in Myanmar, citing her apparent indifference to atrocities committed by the Myanmar military and increasing intolerance of freedom of expression.

“As an Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience, our expectation was that you would continue to use your moral authority to speak out against injustice wherever you saw it, not least within Myanmar itself,” wrote Kumi Naidoo.

“Today, we are profoundly dismayed that you no longer represent a symbol of hope, courage, and the undying defence of human rights. Amnesty International cannot justify your continued status as a recipient of the Ambassador of Conscience award and so with great sadness we are hereby withdrawing it from you.”

Perpetuating human rights violations

Since Aung San Suu Kyi became the de facto leader of Myanmar’s civilian-led government in April 2016, her administration has been actively involved in the commission or perpetuation of multiple human rights violations.

Amnesty International has repeatedly criticized the failure of Aung San Suu Kyi and her government to speak out about military atrocities against the Rohingya population in Rakhine State, who have lived for years under a system of segregation and discrimination amounting to apartheid. During the campaign of violence unleashed against the Rohingya last year the Myanmar security forces killed thousands, raped women and girls, detained and tortured men and boys, and burned hundreds of homes and villages to the ground. More than 720,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh. A UN report has called for senior military officials to be investigated and prosecuted for the crime of genocide.

Although the civilian government does not have control over the military, Aung San Suu Kyi and her office have shielded the security forces from accountability by dismissing, downplaying or denying allegations of human rights violations and by obstructing international investigations into abuses. Her administration has actively stirred up hostility against the Rohingya, labelling them as “terrorists”, accusing them of burning their own homes and decrying “faking rape”. Meanwhile state media has published inflammatory and dehumanizing articles alluding to the Rohingya as “detestable human fleas” and “thorns” which must be pulled out.

“Aung San Suu Kyi’s failure to speak out for the Rohingya is one reason why we can no longer justify her status as an Ambassador of Conscience,” said Kumi Naidoo.

“Her denial of the gravity and scale of the atrocities means there is little prospect of the situation improving for the hundreds of thousands of Rohingya living in limbo in Bangladesh or for the hundreds of thousands of Rohingya who remain in Rakhine State. Without acknowledgement of the horrific crimes against the community, it is hard to see how the government can take steps to protect them from future atrocities.”

Amnesty International also highlighted the situation in Kachin and northern Shan States, where Aung San Suu Kyi has failed to use her influence and moral authority to condemn military abuses, to push for accountability for war crimes or to speak out for ethnic minority civilians who bear the brunt of the conflicts. To make matters worse, her civilian-led administration has imposed harsh restrictions on humanitarian access, exacerbating the suffering of more than 100,000 people displaced by the fighting.

Attacks on freedom of speech

Despite the power wielded by the military, there are areas where the civilian-led government has considerable authority to enact reforms to better protect human rights, especially those relating to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly. But in the two years since Aung San Suu Kyi’s administration assumed power, human rights defenders, peaceful activists and journalists have been arrested and imprisoned while others face threats, harassment and intimidation for their work.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s administration has failed to repeal repressive laws – including some of the same laws which were used to detain her and others campaigning for democracy and human rights. Instead, she has actively defended the use of such laws, in particular the decision to prosecute and imprison two Reuters journalists for their work documenting a Myanmar military massacre.

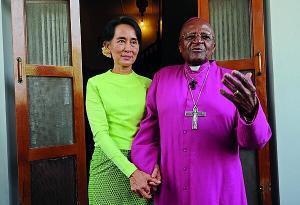

Aung San Suu Kyi was named as Amnesty International’s Ambassador of Conscience in 2009, in recognition of her peaceful and non-violent struggle for democracy and human rights. At the time she was held under house arrest, which she was eventually released from exactly eight years ago today. When she was finally able to accept the award in 2013, Aung San Suu Kyi asked Amnesty International to “not take either your eyes or your mind off us and help us to be the country where hope and history merges.”

“Amnesty International took Aung San Suu Kyi’s request that day very seriously, which is why we will never look away from human rights violations in Myanmar,” said Kumi Naidoo.

“We will continue to fight for justice and human rights in Myanmar – with or without her support.”

‘We don’t need their prize’

Despite her international reputation as a rights icon being in tatters, Aung San Suu Kyi remains defiant as her public support remains unscathed.

Deputy Minister for Information Aung Hla Tun told AFP he was personally sad and disappointed by Amnesty’s announcement and said Aung San Suu Kyi was being treated “unfairly”.

Such moves would only “make the people love her more”, he added.

People on the street in Yangon were defiant.

“Their withdrawal is pretty childish. It’s like when children aren’t getting along with each other and take back their toys,” 50-year-old Khin Maung Aye said.

“We don’t need their prize,” Htay Htay, 60, has been quoted as saying by Channel NewsAsia