Lack of clean energy and power is negatively impacting many lives across Africa, Malawi inclusive. At the first day break of dawn 2018 to date, over 645 million Africans — some two-thirds of the people on the continent — have had no access to energy.

An estimated 600,000 Africans — half of them children die, every year from household cooking fuels air pollution.

In response to the shortage of reliable power, most Africans are finding ways to make do with what they can find, and those who can afford, are using alternative power systems — creating a market for the generator sets business.

Couples like Mr. and Mrs. Roman Mkandawire of Chimeto Trading Limited in Mzuzu are engaged in the business of buying and selling generator sets.

“We have different customers who come to buy what we sell,” the wife explains.

The couple sells petrol and diesel powered generators which are in demand as electricity supply is still unsteady and mostly unavailable in many parts of Malawi.

She continues: “Some of the customers trek from as far as Mutantha in Mzimba district. Most of whom are tobacco farmers.”

In Mzuzu for instance, frequent constant power cuts have become a common phenomenon. While living in a private hostel just meters away from the Mzuzu University campus, Joseph Sichali, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) under-graduate student of the University experienced blackouts, sometimes lasting for several hours.

In Blantyre Malawis commercial city, the situation is no better as some areas are notorious for being in darkness for weeks at a time. So if power cuts can be described as the relative who is not welcome, residents of various communities in Malawi now also consider diesel generator sets as the obstinate mother-in-law that refuses to go back home after paying a visit.

Despite the health and environmental effects of using generators, very few individuals have been able to resist the lure. Lawrence Makhambera is a pensioner in his seventies is one of the few who is not addicted to its use.

He grew up during the colonial era so finds it very difficult to turn on his generator when there is no light as he can barely tolerate the noise, he only uses it on the occasions he has overnight visitors or in a bid to preserve poultry items in his deep freezer when the intervals between power cuts are longer than usual.

But individuals of the younger generation which is growing up to hearing the sounds made by generators have become used to it but are they by this habit turning deaf ears to possible health challenges associated with the habit?

The possible effects are adequately described in a May 15, 2011 report published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine by Niyi Awofesu a medical researcher.

He wrote: “Diesel emissions from domestic generators surpass those from workplaces, trucks, and buses, and pose greater risks to human health and the environment due to proximity to homes and prolonged duration of use. Diesel exhaust contains more than 40 toxic air contaminants, including many known or suspected cancer-causing substances, such as benzene, arsenic, and formaldehyde.”

Babies are also particularly vulnerable in such situations as mothers are warned during ante-natal clinics on potential dangers in the environment.

Blantyre resident Mercy Banda, a middle-class woman in her twenties, describes the steps she took after a previous delivery to protect her first child: “Anytime we put on the generator we made sure that the windows were open and that the silencer is not faced towards the house.”

But even if those steps are capable of reducing the effects, it may not be possible for those of a lower class who live in tightly cramped accommodations as they may have little space to navigate.

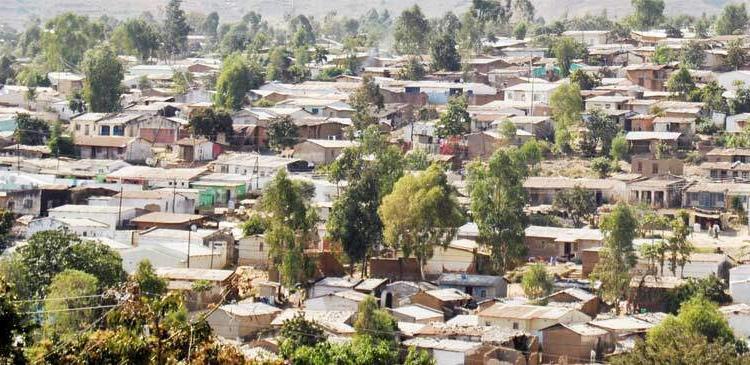

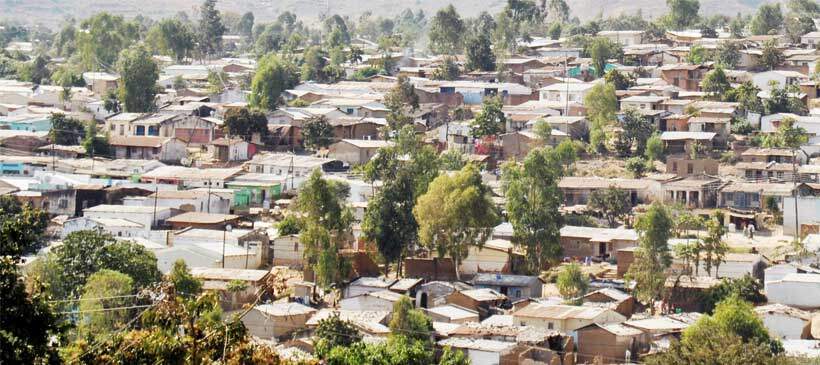

For example, slums in Machinjiri in Blantyre, Chiputula in Mzuzu and Likuni in Lilongwe are built in cramped locations. Also quite a number of the residents who live in the afore-mentioned communities tend to compound issues by taking their babies to the markets and other locations through public transportation which offers no air-conditioning thereby their babies get exposed to more levels of carbon monoxides from exhaust pipes.

Memory Singano, a mother who also attended ante-natal clinic while she was expecting, collaborates Bandas narration.

“At antenatal clinics women are taught on all aspects of helping to ensure the delivery of a healthy baby. They tell us what to eat, the exercises to do and even the lying position to take. We are told that if we are not comfortable, our babies will not be comfortable,” she said.

Judith Chitseko, an obstetrician and Gyneacologist, expands describes relationship between the foetus and the host who is the mother: “The foetus grows inside the uterus. At the embryonic stage when it has already moved through the fallopian tube it attaches itself to the uterus and gets access to the hormones needed to grow while inside the mother. In about eight weeks from the day of conception the heartbeat can be heard with the aid of certain medical implements.”

She goes further by describing how carbon monoxide which is a primary product of generators can affect infants.

“The external environment in which a mother or a mother-to-be finds herself is very important. If she is inhaling very bad air, like fumes from electric generators, it can cause death to both mother and child,” she warned.

This summations infers that even though the use of home electric generators have become quite popular in Malawi and beyond, more care must be taken to protect all lives especially those of unborn babies as well as the newly born.

Taphunzira nawo sitimadziwa kuti zinthunzi zotiwonongaso