A critical examination of most policies created shortly after Malawi’s independence reveals aspects reminiscent of the Thangata system. The introduction of the multiparty system of government also reveals similar aspects. The evolution of these aspects can be traced from pre-colonial to colonial to contemporary Malawi. Ironically, specific modern policies designed to reduce poverty in present-day Malawi are making the situation worse. These policies are exacerbating poverty and corruption in the country.

For those with the ability to analyze and understand policies, it is widely acknowledged that every policy is inherently ambiguous. Policies, particularly the nuanced policy language, are crafted to express policy aims. People with the ability in policy analysis recognize that policy language is nuanced and designed to express specific aims. It is also widely acknowledged that every policy is inherently ambiguous. But if this ambiguity in policy language is not effectively addressed during implementation, it can lead to policy gaps. This can cause confusion. It can also create a fertile ground for abuse and corruption.

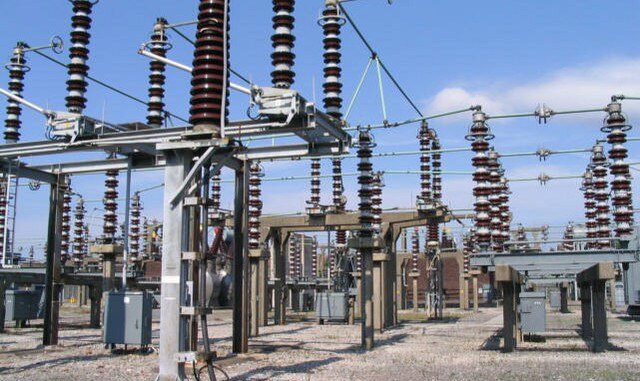

The current policy by ESCOM leaves much to be desired. This policy allows customers to buy electrical equipment like transformers, poles, and wires. It also includes everything needed for ESCOM contractors to connect power from the mainline to a customer’s property. Yet, with the proper adjustments and a commitment to transparency, this policy expedites the power distribution process to customers. It economically empowers local contractors through employment and the provision of services to ESCOM customers.

This policy sounds promising in theory. It is especially promising when explained by those in charge of implementing it. However, it still bears the hallmarks of the pre-colonial and colonial Thangata System. This has dire consequences for the people of Malawi. Take ESCOM, for instance, which was established to provide services to the citizens. However, why should Malawians, already struggling with a low GDP, be required to purchase electrical equipment? This equipment ultimately benefits ESCOM more than the individuals who paid for it. Why should a Malawian, living on just a dollar a day, subsidize ESCOM’s operations? Why should they do this without personally benefiting? ESCOM reaps all the profits. This policy, reminiscent of the Thangata System, places an unjust burden on the already struggling Malawian population.

This new Thangata System is clear in ESCOM and the contractors it employs to carry out these services. These contractors are the ones exposing gaps and inconsistencies in implementing this policy. They are skilled at overquoting unnecessary materials for the work at hand. They often quote for more materials than needed, which they can use on their next project. For instance, they overquote for more poles of different sizes for a distance that only covers around 500 meters. Additionally, they tend to quote for more meters of wire than is needed to tap power from the mainline. These policy gaps create an environment where corruption and bribery become commonplace. We claim to fight corruption, but we blame every government. This blame has existed since the dawn of the multiparty system of government in Malawi.

The perpetuation of the Thangata System due to policy gaps is a grave injustice that demands immediate attention. ESCOM and its contractors contribute to this problem. Hardware shops selling materials needed for the job also contribute. It’s completely unacceptable that shop owners are quoting exorbitant prices, making it impossible for honest Malawians to afford these materials. This kind of exploitation is nothing short of disgraceful.

The economic policies conveyed by this policy are designed to benefit ESCOM rather than Malawians. This needs to change immediately. It’s time for the Minister of Energy and Parliament to thoroughly analyze and revise this policy. They need to make sure it truly benefits Malawians, not just ESCOM.

It’s crucial to acknowledge this fact. If a Malawian purchases electrical equipment, ESCOM can use it to provide services to other customers. In this case, that person should be compensated or become a shareholder in ESCOM. The Thangata System ended in Malawi in 1962. It’s outrageous for a large company like ESCOM to continue exploiting poor Malawians in the name of development and patriotism. Malawian companies should prioritize the interests of their fellow citizens and work for the benefit of Malawians. As Malawians, we are entitled to services. These services should not be tainted by the Thangata System. It is perpetuated by ESCOM, its contractors, and affiliated hardware shops in Malawi.

Long live Malawi, but down with the Thangata System perpetuated by ESCOM and its cronies. It’s time for change, and we must all work tirelessly towards a fair and just system for all Malawians.