The global media, particularly social media, has lately been blown apart with propaganda material or sensational news items aimed at creating discontent against certain public figures and political organisations.

“Fake news” is a popular term coined to describe such deliberate disinformation by peddlers that mostly rely on the Internet (social media) or traditional print and broadcast media for its distribution.

A 2017 Research by Oxford University titled Troops, Trolls and Troublemakers: A Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation, defined cyber troops as government, military or political‐party teams committed to manipulating public opinion over social media. Many cyber troop teams run fake accounts to mask their identity and interests.

Locally, these troops are known as Zigoba. These Zigoba are in some instances responsible for creating “Fake news” aimed at gaining support for their favourite political party or candidates.

Despite some suggestions indicating that the “fake news” has existed for many decades, United States (US) President Donald Trump recently popularized “fake news”, following his constant use of the word while bashing some global news outlets critical of his leadership style.

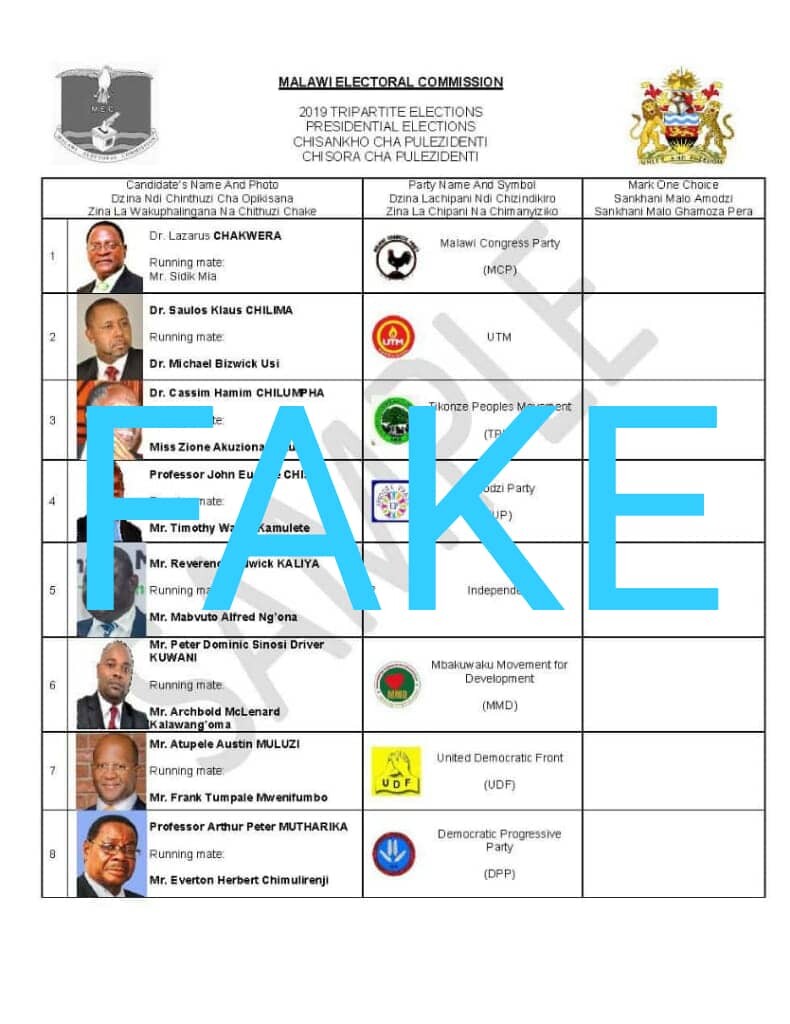

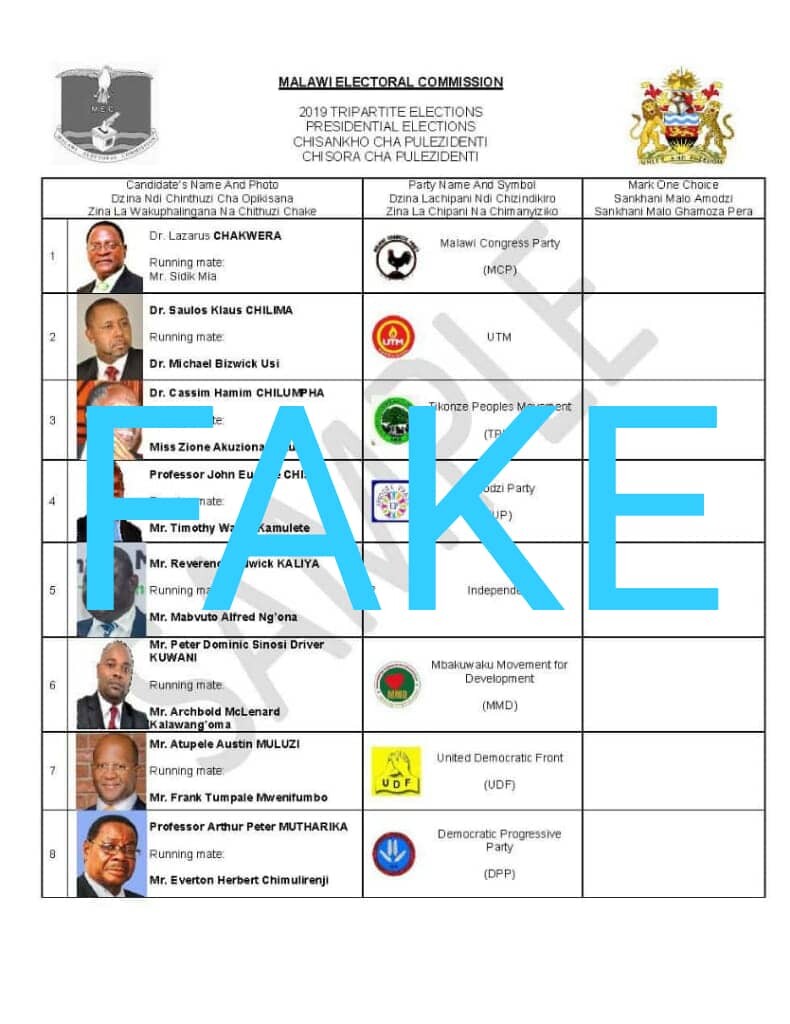

It was, therefore, not surprising on March 21 this year when a fake ballot template bearing faces of eight presidential candidates in the May 21 presidential race flooded the social media (the godfather of “fake news” around the world) courtesy of various local media platforms.

This came barely a month after another fake document made rounds on social media with a forged signature of Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) Chief Elections Officer Sam Alufandika, that depicted a phony list of some candidates it said had been confirmed to contest in the forthcoming Tripartite Elections.

Although these documents have been disowned by MEC, these two incidents are just some of the many cases that have surfaced as Malawi approaches the much-awaited 2019 Tripartite elections.

But Jimmy Kainja, a blogger and lecturer at Chancellor College’s Department of Language and Communication believes that what is fake cannot be news. To him “fake news” is false information deliberately or unknowingly spread.

Kainja adds: “Misinformation does not go together with elections, given that the point of elections is to choose credible leaders to lead a country until the next elections. Therefore, people can only choose credible leaders when they have credible information about the candidates they have to choose from”.

He further stresses that media plays an important role of bringing the candidates and their policies to the electorate so the electorate may make informed choices about the credibility of the candidates before them.

“So the impact of “fake news” is that it leads people to make wrong choices because their choices are based on misinformation,” he says.

But for media scholar Mzati Nkolokosa, whether fake news is good or bad depends on which side of the fence one is standing.

“Candidate A can push unto public domain fake news about candidate B. In that case fake news is good to A and bad to B,” he elucidates.

According to MEC’s Director for Media and Public Relations, Sangwani Mwafulirwa, “fake news” can create chaos and undermine the integrity of the electoral process more especially if emanating from credible media houses and if not controlled, it can discourage people from turning up in large numbers.

He adds: “Everyone all over the world is grappling with fake news, trying all means to contain its spread. The rise on social media has eroded all the gate keeping facilities present before so that nowadays everyone can post what they want on social media and get away with it.

“While many countries and institutions are drafting up laws to curb spreading of fake news, the law on its own is not sufficient. The biggest component to controlling spread of fake news is responsibility. If all people become careful with what they post on social media definitely this would not be a problem. So in Malawi while we may wish to focus and discuss the capacity of the regulating agency to enforce the law, lacking responsibility is highly to blame,” says Mwafulirwa.

In 2016, Malawi Parliament passed the electronic transaction and cyber security bill subsequently assented to by President Peter Mutharika.

Speaking at the briefing of Fibre Project which was aimed at improving Internet services in the country, Mutharika urged Malawians to use social media responsibly.

“The time for those who think they can commit cybercrimes and get away with, is over. We now have a law to make online criminals pay for their crimes,” warned Mutharika.

But three years down the line, Malawians are still experiencing increased cases of the same with no clear sign of an end in sight.

On the flipside, however, some neighbouring countries within the southern African Development Community (Sadc) such as Zimbabwe have resorted to shutting down the internet shutdown as one way of curbing the spread of fake news, particularly during elections.

Such was the case in Zimbabwe’s July 30 elections which were the first ever polls to be held in the country without long time former leader Robert Mugabe who was ousted by the military in November 2017. President Emmerson Mnangagwa defeated opposition leader Nelson Chamisa in the polls.

But according to Kainja, internet shutdowns cannot be a viable solution to such problems especially this time around when Malawians are gearing up for the next general election.

“Being open and forthcoming with information is always the best solution. Internet is a communicative tool and people go there for information, entertain, education and indeed communicating with others, shutting it down is saying people shouldn’t do these things.

“Granted, people also use the internet for criminal purposes but then we should have and I’m sure there are laws that deal with criminal elements. History of internet shutdowns indicates that this only happen during critical periods such as elections because incumbents don’t want people to exercise their rights and freedoms in fear of losing power.

“Any reason given for internet shutdown is just a pretext for something the government wouldn’t want to reveal,” explains Kainja.

He also says people fear the internet because they have something to hide and the internet is an open and empowering tool.

“Fake news is a vehicle for political campaign, so we should accept fake news as something that will be with us forever. And that calls us to develop tools to detect fake news,” concludes Nkolokosa.